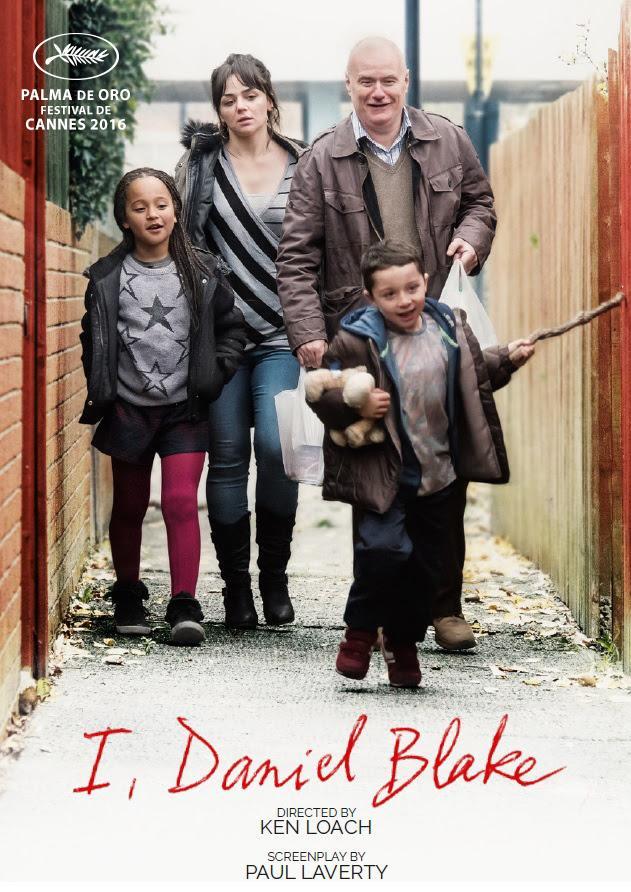

New York Film Festival '16 Review: I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Directed By: Ken Loach

Ken Loach damns the British welfare system with angry ferocious "issue film" and wins a Palme D'Or for his efforts.

Ken Loach, the 80 year old British

stalwart of humanist kitchen-sink cinema, is the most selected film-maker ever at

Cannes and has shown films in competition a record 13 times (including his last

5 films). His selection often draws jeers from some about what dirt does he

have about the Cannes selection committee (and commander in chief Thierry Fremaux), but Loach shut down that conversation

by winning his second Palme D’Or winner for I, Daniel Blake, a decade after

winning his first one (for The Wind That Shakes The Barley (2006)).

And he might as well, as he arrives

with the mad fury of the righteous citizen shaking his fist at the government

that has forgotten him. Paul Laverty, his regular screenwriter, crafts a

scenario that seems like it’s already been seen in any number of “issue film”

over the years. We see an old man, the said Daniel Blake of the title (Dave Johns, wry, tough and human), a

carpenter who suffers a heart-attack and who is caught amid the catch-22 of the

horribly insensitive (as we are told) British welfare system as he is subject

to abject poverty. His misfortunes are relayed by contrasting them with the

setbacks suffered by Katie (a very good Hayley Squires), an unemployed single

mom of two, who has recently moved to Newcastle.

These two inexorably decent

people bond over shared frustrations and defeats as they battle on to lead a

respectable life, something which proves extremely challenging. Even though

Laverty says that the stories are based on real ones that came up through their

research, the film abounds in clichés, old and new, that routinely populate

such “issue films”. The old man who cannot use computers and is stopped in his

tracks by a computer mouse, the single mother sleeping hungry while giving all

the food to her kids, the old man facing trouble to recruit for new jobs are

all tropes we have seen even though Loach and Laverty try their best to make

these situations sting with renewed outrage.

The pattern of the scenario seems

to be to fling every new humiliation at the characters so the situation can get

exponentially worse every time. And some of these indignities can be seen

coming a mile off as the film rushes through them as if through a checklist

almost – when a young man offers to help Katie find a job that he can get her,

it leads to exactly what you would expect. These kind of “issue films” can

often resemble exploitation films, only instead of lopping of the characters’

limbs and body parts, the film-makers chip away at the characters’ self-respect

and self-worth.

That’s not to say that it is a

screaming hysterical woe-be-me film in the vein of say Lee Daniels’ Precious

(2009). Far from it, the film is strongly directed by Loach with his usual unvarnished

visual style. The palette seems even drabber than usual to attend to the grim

story. All scenes are staged with a maximum amount of understatement (George

Fenton is listed as the composer but does not intrude upon any scene to

sensationalize it) and play as they would in real life with life-like

performances from both the lead performers and other members of the cast. This

formal approach can make some of these scenes even more powerful for audiences

and Loach might yet succeed to draw a rise out of you in some scenes, as he

does in the stirring scene where Katie humiliatingly succumbs to hunger in a food bank.

This is an intensely political

film for being such a quietly humble film but does not contextualize the calamity

portrayed in any larger national, financial or sociological terms. It might

make the film more human and more widely dispersible but it can also be akin to

pointing a finger at an injustice and running away. Is the film worthy of the Palme

D’or? I don’t think so but it yet provides a worthy, engaging look at the

plight of many working class people who the government has turned a face away

from and Loach and Laverty are absolutely doing them a service by damning the dehumanizing bureaucracy of a broken welfare system in such a public

way on the world stage. The film should play well for festival audiences and

might specially appeal to British audiences as a shared experience of torment

that many of them go through.

Comments

Post a Comment